- Tue 29 March 2022

- Youth

- #youth, #4-h, #education, #development, #http, #html, #status-codes

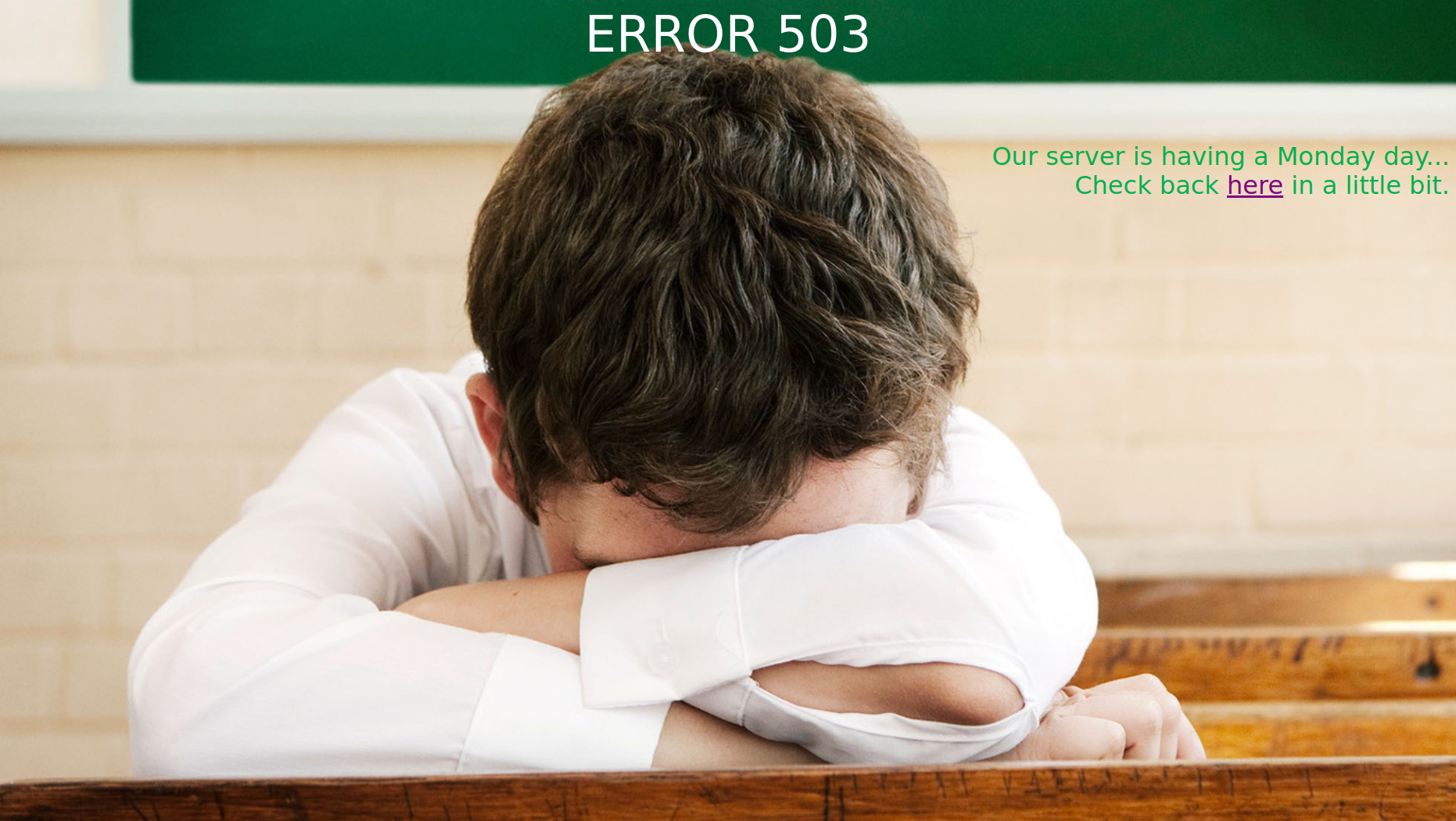

Errors are a given when it comes to computers. Heck, they're a given when it comes to most technology. We're all familiar with the "dreaded 404" that's presented to users when a page or resource can't be found. That doesn't mean that they have to be boring! After all, the text "404" on screen is plain; uninteresting. Wouldn't it be disingenuous to use just plain text for a web-service that's exciting and interesting?

I think it would be!

Enter Youth-Designed Error Pages!

This 404 page was designed by the youth that I'm working with. It gives some flavor to the site when something goes wrong. Admittedly, it's never the goal for things to go wrong, but when it (inevitably) happens, we're ready!

Intent

I wanted to introduce the 4-H member who's helping me to a little "old-fasioned" web design. Crafting plain HTML with CSS and putting it all together

for the specific purposes of showing errors, but that's not exactly easy when you're just starting out. I also wanted to capture some of the "flare" and

creativity that 4-H members always seem to have. After all, isn't part of the fun of any development project putting in the easter eggs? I think so!

So, that leaves me with two clear goals:

- Youth-designed static HTML/CSS

- Capturing creativity of youth

Tools

Like I said... It's not easy to just spin HTML off the cuff when you've never done any of it before in your life! Especially when we're talking about full- fledged pages that have pretty formatting and the like. What to do... what to do...

Enter: Microsoft Word.

Yep, that's right. The ultimate IDE... Well, something like that.

Anyway, Microsoft Word may not be a good IDE by most (sane) people's standards, but that doesn't mean that we can't use it for a little visual assistance. One thing that Word does have going for it in this space is the ability to easily format pages with text, images, formatting, and more. All in a convenient interface. After all, isn't that the reason that most of the world uses MS Word instead of LaTeX?

With this convenience, it's pretty easy to put some images together, add some text, center it how you want, and publish! Did I mention two key features?

- Microsoft Word has an web-page viewing mode to present the page as how it might appear in a browser

- Microsoft Word natively supports saving a file as

*.htm/*.html

That means that I could get anyone started with creating the pages, and worrying less about the HTML and more about how they want the pages to look.

Excellent.

Bumps in the Proverbial "Information Superhighway"

Well, that's all well and good; quite simple really, but here's where the rubber hits the 10101001010010101010010101010010100010101111...

When it comes time to publish these pages, it's pretty simple, the whole repository that we're working in is based around the separation of a frontend and a backend. The backend houses all the Python goodness, and all of the static and template files that are rendered and loaded for web-serving. That means that if we want to host specific files for error pages, we can split them up and distribute them accordingly into the backend directories like shown below.

backend

|-- static

| |-- someErrPage_files

| | |-- (css/js/other supporting files go here)

| |

| |-- someOtherErrPage_files

| |-- (css/js/other supporting files go here)

|

|-- templates

| |-- someErrPage.html

| |-- someOtherErrPage.html

|

|-- main.py

When we "export" or save the rendered error page from Word, we end up generating a single HTML file, and a folder full of supporting files. Everything

from CSS, to XML, to images, and more. Since that's all static stuff, we can stick it in a sub-folder under the backend/static directory. The plain HTML

file, on the other hand, goes to the backend/templates folder where it will be pulled from by Jinja in Python and rendered.

Key to all of this, is getting paths right. After all, pirates didn't find their treasure if they meant "paces" when they said "leagues" right?!

In much the same way, when Word generates those files, it assumes a certain path. It assumes that the folder containing all support files is colocated with the HTML file, in the same directory. Clearly, here, they are not.

This separation is for good reason though, all of the support files are static, they're not templates. We wouldn't ever want Jinja to attempt rendering

any one of them, so they go in the static directory. Simple as that. Now, the Python server already knows to route accordingly for static files, after

all, early on, it uses a static router for FastAPI to do the lifting here, and it also sets up the templates structure accordingly so as to make Jinja

rendering easy:

# Application Base

app = FastAPI()

TEMPLATES = None

@app.on_event("startup")

async def startup_event():

"""Event that Only Runs When App is Starting"""

global TEMPLATES

# Mount the Static File Path

app.mount("/static", StaticFiles(directory="static"), name="static")

TEMPLATES = Jinja2Templates(directory="templates")

Notice however, that for FastAPI to "catch" any such requests, it needs to see a URI with the prefix of /static. Are you beginning to see the problem?

That's right, because MS Word doesn't include that prefix, the web-client will unknowingly ask for files that don't exist, and FastAPI will throw up its hands in defeat. Now, that's not all bad, since they're all just plain files, we can edit the HTML quite easily, and with a tweak or two, we can add the prefix where it's needed. It took me a bit to figure out exactly where this needed to be done, but when I did, it was very straight forward!

Results

I'll let you be the judge here. You've already seen the 404, but here's the 501 and 503:

I'm very satisfied with the results; they pages are clever, cute, and most of all, they're genuine and showcase the very esence of learning and exploring with 4-H. That all makes me very happy.

Making Them Stand Out

I really wanted to be able to show off these pages whenever I want. After all, it would kinda suck to only be able to see them when there's a legitimate error. That would make it very difficult to show them to passers-by! So, we did a little function-crafting!

# HTTP Error Response

@app.get("/404", response_class=HTMLResponse)

async def page404(request: Request):

return TEMPLATES.TemplateResponse("404.htm", {"request": request})

# HTTP Error Response

@app.get("/501", response_class=HTMLResponse)

async def page501(request: Request):

return TEMPLATES.TemplateResponse("501.htm", {"request": request})

# HTTP Error Response

@app.get("/503", response_class=HTMLResponse)

async def page501(request: Request):

return TEMPLATES.TemplateResponse("503.htm", {"request": request})

# HTTP Exception Handlers

@app.exception_handler(StarletteHTTPException)

async def custom_http_exception_handler(request: Request,

exc: StarletteHTTPException):

if exc.status_code == 404:

return await page404(request=request)

elif exc.status_code == 501:

return await page501(request=request)

elif exc.status_code == 503:

return await page501(request=request)

See here, that we were able to create three unique web-endpoints with FastAPI for each of the error pages, and then we could wrap them in the single error

handler. This means that when a user goes to https://develop.idaho4h.com/404 they actually see the 404 page without generating a real 404. The same is

true for the other two errors, making the whole thing pretty slick, indeed.

Guess I'm tooting my own horn pretty loudly, at this point, aren't I?

In conclusion, it's been lots of fun getting to work with youth to make these custom error pages and show them off! It really helps demonstrate the work that this 4-H member has put in!